Lithography and Aloys Senefelder

Lithography, a printing technique invented by the German Aloys Senefelder in 1801, is based on surface interactions, even though the chemistry of surface interactions was not understood at the time. Using the macroscopically evident fact that waxes and greases repel water, a template for ink printing could be easily created.

The first step in the process was to cut a design through a thin mask material. This mask is then laid over the surface one wishes to imprint an image. A greasy or waxy material is spread over the mask and the material only comes in contact with the surface through the cutout design on the mask. The surface is wetted with water and then ink in applied.

The oil containing ink is repelled by the wet surface, yet is absorbed by the water free waxy areas. Once inked, the surface is let to dry and the image is in place. The entire process is possible because of the surface interactions of the polar and non-polar materials used. This technique is very simple, cheap, and efficient.

It is extremely effective for the printing of artwork because the non-precise nature of the wax-water repulsion would create prints with a painterly appearance. However, this appearance is not effective for industrial printing processes. Thus, there has been research ever since into techniques based upon the basic lithographic process but that allow for greater precision.

Lithography, a printing technique invented by the German Aloys Senefelder in 1801, is based on surface interactions, even though the chemistry of surface interactions was not understood at the time. Using the macroscopically evident fact that waxes and greases repel water, a template for ink printing could be easily created.

The first step in the process was to cut a design through a thin mask material. This mask is then laid over the surface one wishes to imprint an image. A greasy or waxy material is spread over the mask and the material only comes in contact with the surface through the cutout design on the mask. The surface is wetted with water and then ink in applied.

The oil containing ink is repelled by the wet surface, yet is absorbed by the water free waxy areas. Once inked, the surface is let to dry and the image is in place. The entire process is possible because of the surface interactions of the polar and non-polar materials used. This technique is very simple, cheap, and efficient.

It is extremely effective for the printing of artwork because the non-precise nature of the wax-water repulsion would create prints with a painterly appearance. However, this appearance is not effective for industrial printing processes. Thus, there has been research ever since into techniques based upon the basic lithographic process but that allow for greater precision.

More on Lithography and Aloys Senefelder

The Rise of the Machines

The Stanhope Press -

Lord Charles Stanhope (1753-1816), an English philanthropist, conceived in 1795 for the first time a hand printing press totally built in iron.

With new improvements in pressing and ink systems these printing press permits one production of 100 exemplars per hour. The Stanhope Press -

Lord Charles Stanhope (1753-1816), an English philanthropist, conceived in 1795 for the first time a hand printing press totally built in iron.

With new improvements in pressing and ink systems these printing press permits one production of 100 exemplars per hour.

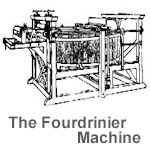

The Fourdrinier Machine - Papermaking machine patented by the Fourdrinier brothers Henry and Sealy in England in 1803. On the machine, liquid pulp flows onto a moving wire-mesh belt, and water drains and is sucked away, leaving a damp paper web. This is passed first through a series of steam-heated rollers, which dry it, and then between heavy calendar rollers, which give it a smooth finish.

Such machines can measure up to 90 m/300 ft in length, and are still in use. The Fourdrinier Machine - Papermaking machine patented by the Fourdrinier brothers Henry and Sealy in England in 1803. On the machine, liquid pulp flows onto a moving wire-mesh belt, and water drains and is sucked away, leaving a damp paper web. This is passed first through a series of steam-heated rollers, which dry it, and then between heavy calendar rollers, which give it a smooth finish.

Such machines can measure up to 90 m/300 ft in length, and are still in use.

A Comparison of Printing Presses . . .

WOODEN PRESSES -

Gutenberg's wooden printing press (left image) was based on the screw or binding press used in other trades like winemaking and metalworking. Appearing in the early to mid 15th century, the printing press made it possible to obtain sharp letters and to print both sides of a sheet. The wooden press did have drawbacks, however, among them its limited strength and the difficulty of manipulating its parts. Improvements -- both minor and major -- to this basic model began almost immediately after its appearance. WOODEN PRESSES -

Gutenberg's wooden printing press (left image) was based on the screw or binding press used in other trades like winemaking and metalworking. Appearing in the early to mid 15th century, the printing press made it possible to obtain sharp letters and to print both sides of a sheet. The wooden press did have drawbacks, however, among them its limited strength and the difficulty of manipulating its parts. Improvements -- both minor and major -- to this basic model began almost immediately after its appearance.

IRON PRESSES - The development of the iron hand press (shown on the right) in the early 19th century resulted in a press that was capable of much greater impressional strength. The first of these presses was the Stanhope press, designed by the Earl of Stanhope in 1800. Production surpassed that of the wooden presses and it became possible to print 100 -- and not long after, far more -- pages in an hour.

PLATEN PRESS - The platen press (shown on the left) was developed in the mid 19th century. Manufactured in varying sizes from floor models to table tops, there were two main types of platen press. The light jobbing platen, credited primarily to George P. Gordon, was used for small items such as business cards, envelopes, and circulars. The heavy or art platen was much larger and used for all kinds of work.

In both types, printing was completed by the platen closing to meet the type bed, in a similar action to that of a hinge. Early presses were powered by foot-treadles, and steam power and then electric motors were eventually added for even greater speed.

~ Source: http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/presses/t15-451-e.html PLATEN PRESS - The platen press (shown on the left) was developed in the mid 19th century. Manufactured in varying sizes from floor models to table tops, there were two main types of platen press. The light jobbing platen, credited primarily to George P. Gordon, was used for small items such as business cards, envelopes, and circulars. The heavy or art platen was much larger and used for all kinds of work.

In both types, printing was completed by the platen closing to meet the type bed, in a similar action to that of a hinge. Early presses were powered by foot-treadles, and steam power and then electric motors were eventually added for even greater speed.

~ Source: http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/presses/t15-451-e.html

Chromolithography

During the nineteenth century, lithographers perfected the art of printing in color by using multiple stones to achieve very complex colored images through a process known as chromolithography. Cheap color printing was then available for the first time in the history of printing. While the most pervasive use of chromolithography was in advertising, it was also used extensively for making popular prints as well as for scientific and medical illustrations.

To better understand the chromolithographic process, view (on your left) selected progressive proofs of Prang's Prize Babies,

a popular print of the late nineteenth century made from 19 stones. To better understand the chromolithographic process, view (on your left) selected progressive proofs of Prang's Prize Babies,

a popular print of the late nineteenth century made from 19 stones.

More on this link: http://seeing.nypl.org/planographic.html

Ottmar Mergenthaler and the Linotype Machine

Ottmar Mergenthaler (Born May 10 1854 - Died Oct 28 1899)

Ottmar Mergenthaler (Born May 10 1854 - Died Oct 28 1899)

Mergenthaler's invention of the linotype composing machine in 1886 is regarded as the greatest advance in printing since the development of moveable type 400 years earlier.

Mergenthaler's machine enabled one operator to be machinist, type-setter, justifier, typefounder, and type-distributor.

Since the machine was first used in 1886 by the New York Tribune, great improvements on its design have been made. Probably more than 1,500 separate patents have been taken out in connection with it.

The Linotype Machine - 1886 The Linotype Machine - 1886

The Linotype Machine: Thomas Edison called it the "Eighth Wonder of the World"

"Ottmar, you've done it again! A line o' type!" Whitelaw Reid, publisher of the New York Tribune, exclaimed on July 3, 1886, when Ottmar Mergenthaler demonstrated his new Linotype machine. The Linotype quickly brought about a revolution in the printing industry.

More than 400 years after Johann Gutenberg invented moveable type, a process that allowed printers to set type by hand a letter at a time, the Linotype allowed printers to set a complete line of type, using the Linotype's 90-character keyboard. Because the Gutenberg process was so slow, most large newspapers consisted of no more than eight pages. But with the advent of the Linotype, that was to change quickly, and within 20 years Linotypes were in use in every state.

Mergenthaler's invention measured 7 feet tall, 6 feet wide and 6 feet deep. It allowed newspapers to compose pages four to five times faster and caused thousands of hand compositors to lose their jobs. A skilled Linotype operator could cast four to seven lines of type a minute. The Linotype operator's key strokes told the machine which letter molds to retrieve from the magazines and the machine assembled a row of metal molds, or matrices, that contained imprints of those characters. Then, the machine poured molten lead into the matrices and the result was a complete line of newspaper type, but in reverse, so that it would read properly when it transferred ink to the page. The machine automatically restored the matrices to the magazines after the lead was poured.

Learn how the Linotype Machine Operates . . .

|